The Memento Problem

Why your AI agents need a system, not a bigger brain

There's a scene in Christopher Nolan's Memento that I think about constantly when working with AI agents.

Leonard, the protagonist, wakes up in a motel room. He doesn't know how he got there. He doesn't remember checking in, doesn't remember the drive, doesn't remember anything from the past few hours. But he's not confused. He's not panicking. He calmly checks his pockets, reads the notes he left himself, examines the Polaroids with handwritten captions, and pieces together enough context to act.

Leonard has anterograde amnesia—he can't form new memories. Every few minutes, his slate is wiped clean. And yet he functions. He pursues complex goals across days and weeks. He adapts to new information. He makes progress.

How?

Not by having a better brain. By having a better system.

The Amnesia Everyone Ignores

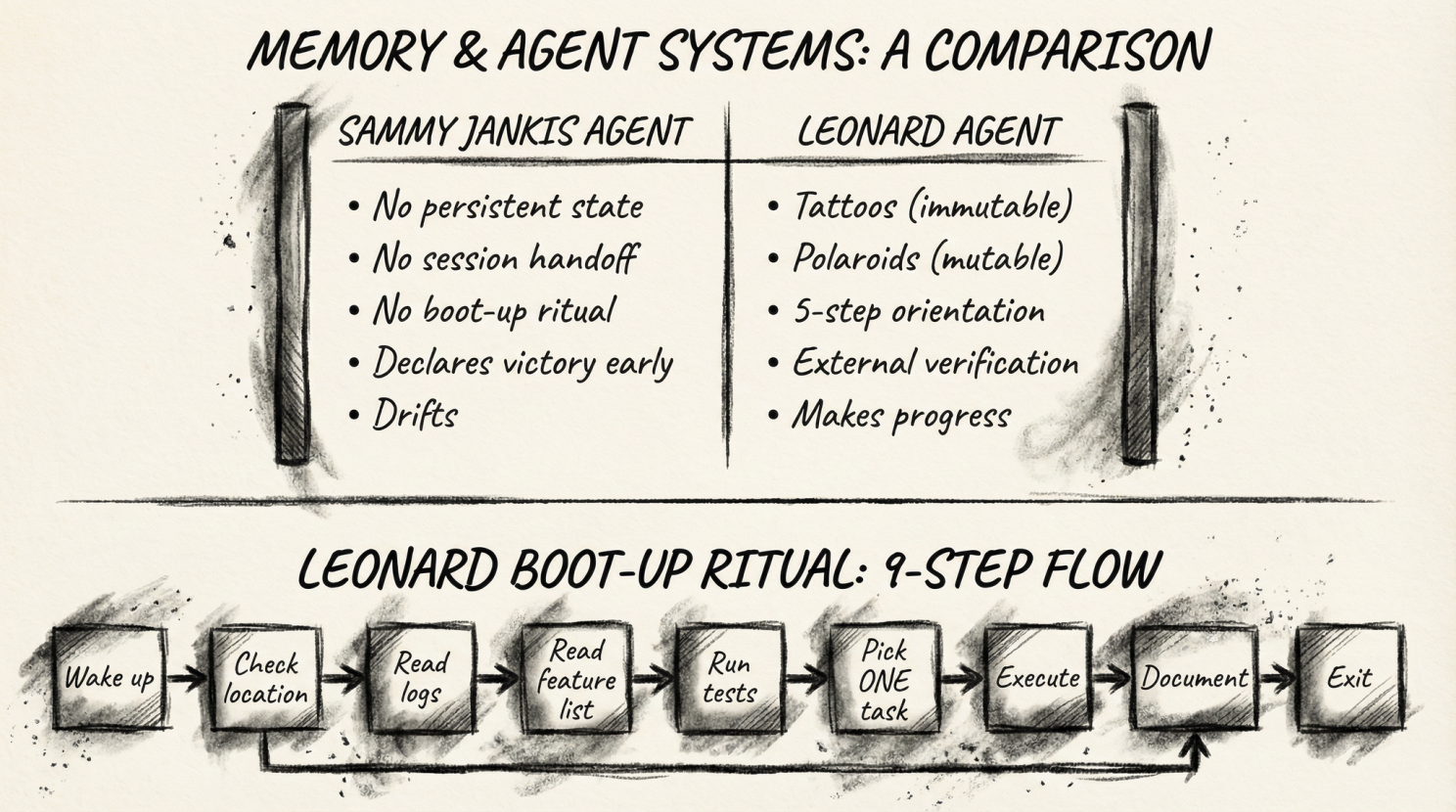

Here's the uncomfortable truth about AI agents: they're all Leonard. Every single one of them wakes up with no memory of what happened five minutes ago. They have tremendous capability and absolutely no continuity.

Most teams respond to this by trying to give their agents bigger brains. Longer context windows. More parameters. Better reasoning. This is like trying to cure Leonard's condition by teaching him speed-reading. It misses the point entirely.

Anthropic recently published research that confirms what anyone who's built production agents already knows. Their engineers, attempting to build a clone of claude.ai using AI agents, documented the exact failure modes you'd expect from an amnesiac with a tool belt.

First failure mode: the agent tries to do everything at once. It attempts to complete the entire project in a single session, like Leonard trying to solve the murder in one caffeine-fueled night. It runs out of context mid-implementation, leaving the next session to inherit half-finished code and no documentation. The next agent wakes up in that motel room, looks around at the mess, and has no idea what any of it means.

Second failure mode: the agent declares victory prematurely. It looks around, sees that some progress has been made, and announces that the job is complete. Without external verification, it has no way to know whether it's actually done or just feels done. Leonard would recognize this problem—it's why he tattooed the crucial facts on his body. You can't trust your own judgment when your memory resets.

Polaroids and Tattoos

Leonard's system has layers. Some information is ephemeral—written on Polaroids that might get lost or destroyed. Other information is permanent—literally tattooed on his skin. The hierarchy matters. The tattoos are facts he's verified and committed to. The Polaroids are working memory, context that helps him navigate but isn't gospel.

The Anthropic team discovered they needed the same architecture. They call it the "initializer and coding agent" pattern, but it's really just Leonard's system translated into software.

The initializer runs once at the start of a project. It creates the equivalent of Leonard's tattoos—a comprehensive feature list with over 200 items, each marked as "failing" until proven otherwise. It establishes a progress file. It writes the boot-up script. It creates the initial commit. These artifacts are permanent. They persist across sessions. They are the source of truth that no individual agent can contradict.

The coding agent is Leonard waking up in the motel. Every session, it performs the same ritual:

- Check the current directory (where am I?)

- Read the git logs and progress files (what happened before I woke up?)

- Read the feature list (what's the mission?)

- Run the boot-up script (get the environment working)

- Run a basic test (is everything still functional?)

Only after this orientation does it pick a single task and execute. Then it updates the progress file, commits its changes, and exits. It doesn't try to solve everything. It solves one thing, documents what it did, and hands off cleanly.

This is the Polaroid system. Each session creates a snapshot: here's what I found, here's what I did, here's what's next. The next agent will wake up, check the Polaroids, and know exactly where to pick up.

The Tattoo You Can't Remove

Anthropic uses a phrase that made me laugh out loud: "It is unacceptable to remove or edit tests because this could lead to missing or buggy functionality."

This is the tattoo. This is the fact so important that it's permanently inscribed, immune to the whims of any individual session.

They use JSON instead of Markdown for the feature list specifically because the model is less likely to inappropriately modify JSON. They've learned, probably painfully, that an agent will rationalize editing its own constraints if given the chance. "This feature isn't really necessary." "We can skip this test." "The requirements have changed."

Leonard has the same problem. In Memento, he eventually discovers that he's been manipulating his own system—destroying Polaroids, writing misleading notes, even tattooing lies on himself. The system only works if it's tamper-proof. The agent only works if its core constraints are inviolable.

The feature list can only be modified in one direction: from failing to passing. Features cannot be removed. Descriptions cannot be changed. The project is done when every feature passes—not when the agent decides it's done, but when the external, immutable checklist says so.

The Clean Handoff

There's a principle in Memento that doesn't get discussed enough: Leonard is meticulous about leaving things in a state his future self can understand. The Polaroids have captions. The notes are clear. The system depends on each "session" leaving good documentation for the next.

Anthropic articulates this as: "Leave the codebase in a state that would be appropriate for merging to a main branch." No major bugs. Orderly code. Good documentation. A developer—or another agent—could begin work immediately without first having to clean up an unrelated mess.

This isn't just good hygiene. This is the foundation of trust between sessions. Leonard's system falls apart if past-Leonard leaves chaos for future-Leonard. Agent systems fall apart the same way.

Every session is a guest in the codebase. Leave it cleaner than you found it.

The Real Moat

Here's the strategic insight that I think most people miss.

The AI models are becoming commoditized. They'll keep improving, but they'll improve for everyone. GPT-5, Claude 4, Gemini Ultra—they'll all be available to your competitors. The model is not your competitive advantage.

The system is your competitive advantage.

Leonard's brain isn't special. What's special is the infrastructure he's built around it—the Polaroids, the tattoos, the rituals, the verification systems. Another amnesiac with the same brain but no system would be helpless. Leonard, despite his condition, is functional and even dangerous.

Your agents are the same. A generic model with generic prompts will produce generic results. The value is in the specific artifacts, the specific workflows, the specific rituals that allow your agents to function as a coherent system rather than a collection of amnesiacs waking up confused in motel rooms.

Anthropic puts it plainly: the magic is not in the model. The magic is in the harness.

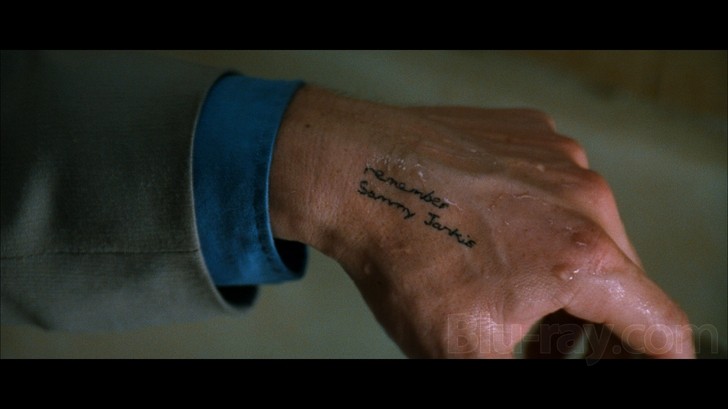

Remember Sammy Jankis

In Memento, Leonard has a mantra he repeats to himself: "Remember Sammy Jankis." Sammy was another amnesia patient who, unlike Leonard, never developed a system. He just drifted, helpless, making the same mistakes over and over. He's a warning.

I've watched teams build Sammy Jankis agents. Powerful models with no structure. Long context windows filled with noise. Sophisticated reasoning applied to the wrong problems because no one established what the problems actually were. These agents drift. They make the same mistakes over and over. They declare victory when they haven't won. They forget what they did five minutes ago.

Don't build Sammy. Build Leonard.

Create the tattoos—the immutable constraints, the feature lists that can't be edited, the definitions of done that can't be negotiated. Create the Polaroids—the session logs, the progress files, the handoff documentation. Create the rituals—the boot-up sequence, the verification checks, the clean exit.

The condition can't be cured. Your agents will always be amnesiacs. But with the right system, that doesn't matter. Leonard solved a murder. Your agents can ship software.

The secret isn't in their heads. It's in what they write down.